The SLA illusion: AWS pays $470K, Salesforce loses $47M

AWS CloudFront promises 99.99% uptime. The SLA says if monthly uptime falls between 99.0% and 99.9%, you get a 10% credit on your CloudFront spend. On February 10, 2026, CloudFront was down for 134 minutes. That's 99.69% monthly uptime. Salesforce qualifies for the 10% credit.

Estimating conservatively, Salesforce spends $4.7 million per month on CloudFront (based on typical enterprise CDN contracts and public traffic data). The 10% SLA credit: $470,000.

But Salesforce didn't lose $470K during the outage. According to Salesforce's Q4 2025 10-K, the company generates $73.2 billion annually — $8.35 million per hour on average. During business hours, when this outage hit, that number spikes 2.5x due to enterprise usage concentration. Over 2 hours and 14 minutes, Salesforce lost approximately $47 million in unprocessed transactions, failed deals, and SLA breaches with its own customers.

$47 million in losses. $470,000 in compensation.

The AWS SLA covers 1% of the actual cost. The customer eats the other 99%. And this is Salesforce — one of the largest companies in the world with the financial cushion to absorb the hit. For a startup or mid-sized SaaS, an outage of this magnitude can be terminal.

Cloud SLAs aren't insurance against losses. They're discounts on next month's bill. The illusion of enterprise protection.

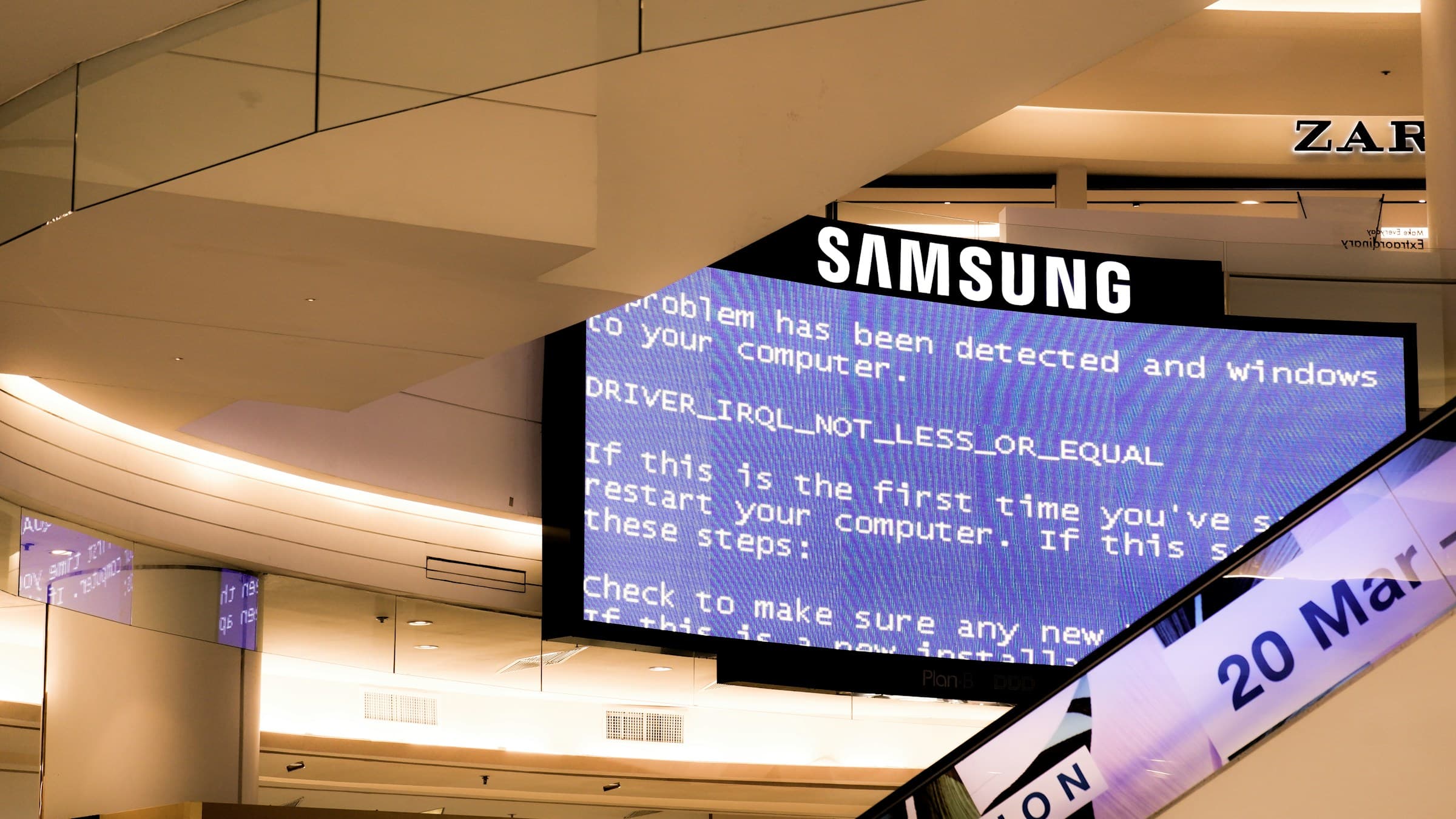

February 10, 2026: The 134-minute outage that exposed shared fate architecture

At 18:47 UTC on February 10, 2026, AWS CloudFront stopped resolving DNS. Over the next 134 minutes, Salesforce CRM, Anthropic's Claude API, Adobe Creative Cloud, Discord, Twitch, Slack integrations, Zendesk, and a list of 20+ platforms that depend on AWS infrastructure went dark.

This wasn't an isolated CloudFront failure. The cascade dragged down 8 AWS services: Route 53, API Gateway, WAF, Shield, Certificate Manager, Secrets Manager, and Systems Manager. According to ThousandEyes data, 87% of CloudFront's 600+ edge PoPs went offline. This wasn't a regional issue. It was systemic.

AWS published a terse statement on its Health Dashboard acknowledging "DNS resolution issues affecting CloudFront." Two hours and 14 minutes later, at 21:01 UTC, service was restored. No detailed technical explanation. No public post-mortem. Just the standard "we have identified and mitigated the issue."

The numbers tell a different story.

| AWS Service | Role in CloudFront | Impact of DNS Failure |

|---|---|---|

| Route 53 | DNS resolution for distributions | No DNS, no traffic |

| Certificate Manager | SSL/TLS validation | Certificates unreachable, connections rejected |

| API Gateway | Backend for serverless apps | Endpoints unreachable |

| WAF | Malicious traffic filtering | Rules unapplied without requests |

AWS's multi-AZ architecture protects against hardware or individual data center failures. It doesn't protect against failures in global control plane services. Route 53, API Gateway, Certificate Manager: all are shared global dependencies. A failure in Route 53 doesn't stay contained in us-east-1. It affects all regions simultaneously because DNS is, by design, global.

Why AWS redundancy failed: Global control plane dependencies

CloudFront depends on Route 53 to resolve DNS records for its distributions. When Route 53's authoritative nameservers failed health checks, the CNAME resolution chain broke. CloudFront edge PoPs started rejecting requests because they couldn't validate SSL certificates hosted in Certificate Manager — which also uses Route 53 for internal lookups.

This is what AWS calls "shared fate" architecture. When a global control plane service fails, the blast radius is unlimited. Multi-AZ doesn't help. Regional failover doesn't help. The architecture multiplies the impact.

Cloudflare, by contrast, operates with isolated failure domains. If one PoP goes down, the others stay operational. AWS, with its global shared services (Route 53, Certificate Manager), multiplies the blast radius of a single point of failure.

This wasn't the first time. In December 2021, a failure in us-east-1 took services down for 7 hours. In February 2017, a typo in an S3 script caused 4 hours of downtime. In November 2020, Kinesis dragged multiple services offline for 8+ hours.

The pattern is clear: when an AWS control plane service fails, the cascade is inevitable.

The multi-cloud dilemma: $2.8M setup vs. actuarial risk

The obvious solution is multi-cloud: use Cloudflare as a secondary CDN, maintain external DNS (e.g., NS1 or Dyn), configure circuit breakers that automatically redirect traffic on failure. Netflix does it. Spotify does it. Any platform with critical uptime should do it.

But according to InfoQ analysis of enterprise multi-CDN architectures, the initial setup cost is $2.8 million for a mid-sized organization: configuration migration, duplicate SSL certificates, DNS failover logic, disaster recovery testing, SRE team training.

And the ongoing overhead is 15-20%: duplicate CDN costs (even though Cloudflare is 40% cheaper than CloudFront, you're still paying two providers), operational complexity (two dashboards, two log systems, two update cycles), and additional failover latency (typically 30-90 seconds for DNS propagation).

For a startup or growth-stage SaaS, $2.8M is prohibitive. They prefer to accept the actuarial risk: the probability of a 2+ hour outage is low (4 in 5 years = ~16% annually). The expected cost of downtime ($47M × 16% = $7.5M annualized for a Salesforce-sized company, much less for a startup) doesn't justify the immediate capex of multi-cloud.

Let's be real: AWS has created a model where 87% of customers choose to accept concentration risk because the alternative is financially unviable until they're already large enough to afford redundancy.

And when they reach that size, vendor lock-in (Lambda functions, RDS configs, IAM policies, VPC peerings) makes migration even more expensive. It's a perverse incentive: AWS profits more the more you depend on them, and that dependency makes it progressively costlier to leave.

Until the DNS fails and you lose $47 million in an afternoon. Then you realize the SLA was never insurance. It was just marketing with fine print.

4 major outages in 5 years: This is the pattern, not the exception

AWS controls 32% of the global cloud infrastructure market according to Gartner (Q4 2025). One in three internet services depends on AWS. When AWS falls, it drags down a third of global cloud computing with it.

And AWS falls more often than its marketing suggests. According to the AWS Post-Event Summaries (PES) archive, in the last 5 years there have been 4 outages longer than 2 hours:

- November 2020: Kinesis failure in us-east-1 takes down Cognito, CloudWatch, Alexa. 8+ hours of downtime.

- February 2017: Typo in S3 command deletes control plane servers. 4 hours offline.

- December 2021: us-east-1 failure affects Lambda, RDS, ECS. 7 hours of chaos.

- February 2026: This CloudFront outage. 2 hours 14 minutes.

And the competition? Google Cloud Platform had 0 outages longer than 1 hour in 2024-2025 according to public incident records. Cloudflare, with its 1.1.1.1 DNS network decoupled from its CDN, also reports 0 multi-hour outages in the same period.

This isn't an exceptional event. It's systemic risk architecture operating as designed.